Why to study the fly's brain?

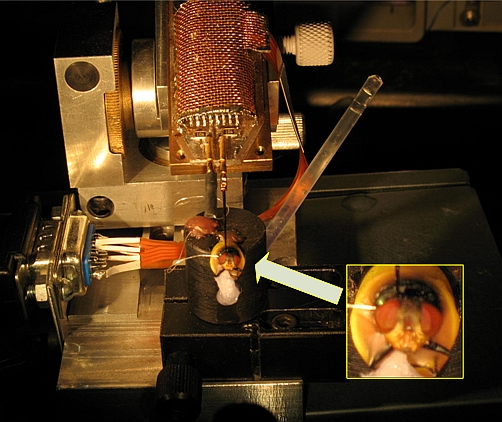

The tiny brain of the Diptera order blowfly has, despite of its size, millions of neurons consisting a real Complex System. It is, however, infinitely simpler than the brain of primates, and one of the few biological systems where it is possible to register the neuronal activity for a few days (Figure 1), allowing very controlled experiments. This facts, together with two decades of years and neuroanatomial researches of these animals, we got a mature system to apply different sucessful techniques from physics. This system based on organic molecules must function properly despite of the unavoidable thermal noise, makin the use of probabilistic tools fundamental for the researcher.

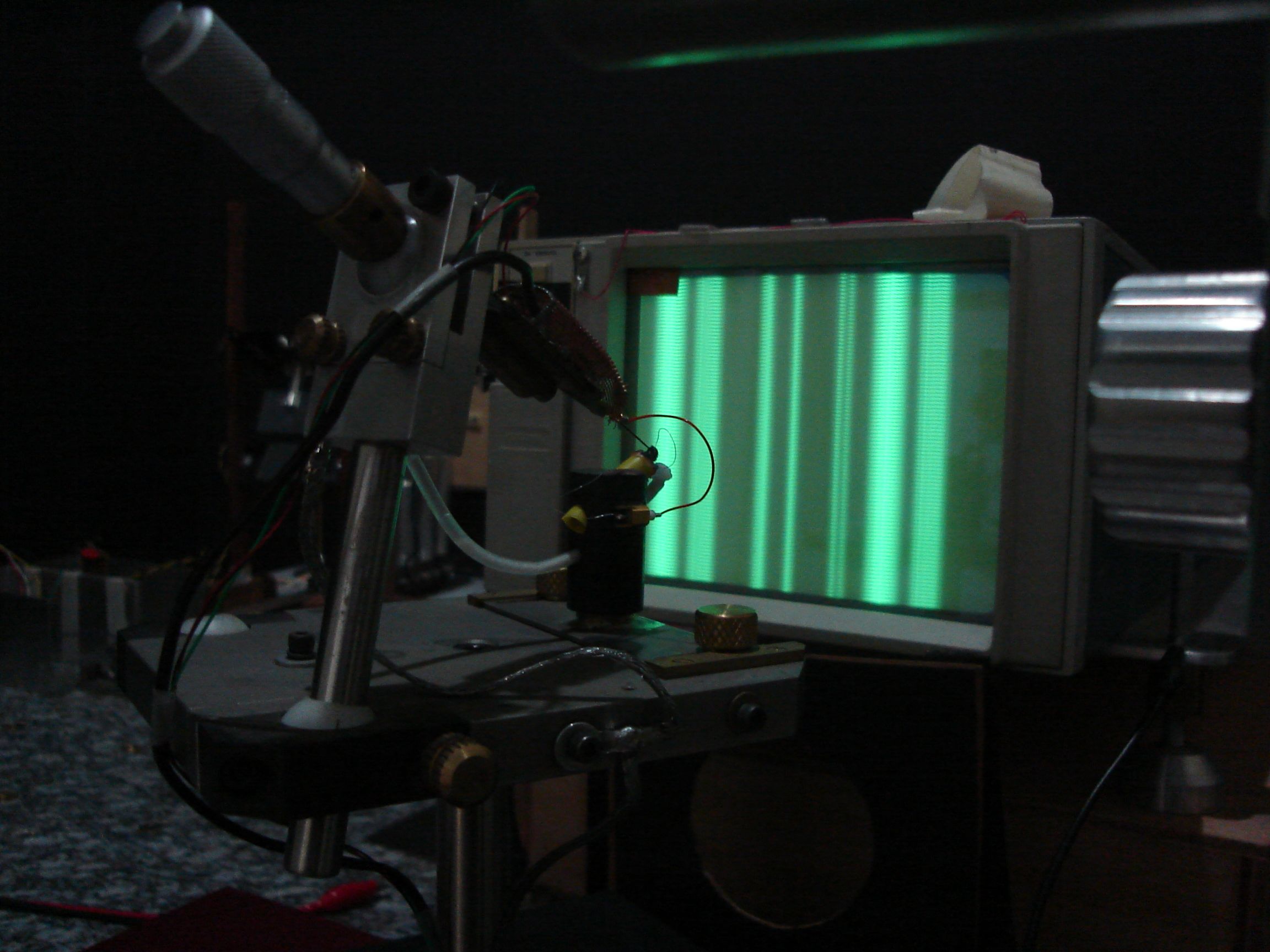

Our main goal is to study the information transfer(In Shannon's sense) on the optical duct of the fly (Figure 2). This process begins on the ommatidium of the composite eye, flowing by the photoreceptors and the early processing stages: lamina, medulla, lobula and lobula plate. The anatomy of this pathway is weel known on its beginning - the photoreceptors - and on its end - the lobula and the lobula plate - less known on the medulla, where there are a lot of small cells. On the lobula plate there a series(about 20) of giant neurons that monitors the movement arount 3 axes - horizontal, verical and longitudinal. They are responsible fot stabilizing the flight and they have been classified by Haysen and it collaborators.

In particular, the wide field neuron H1 is responsible to integrate all the verticular movement stimuli, making it sensible for horizontal movements. In the lobula plate there are neurons, like the H1 or the V2 - responsible to monitor rotations between a horizontal axis, which the answer to stimuli is characterized by a sequence o identical pulses, a spike train. There are, actually, two H1 neurons, one on each hemisphere on the rear of the fly's head, each one responding to a single direction. The H1 neuron responds to visual stimuli that moves on the horizontal direction. the ipsilateral to the ones thar move to one direction, and the counterlateral the the oposite one.

To register this voltage pulses, the living fly is fixed with wax and a tungsten electrode is placed extracellularly (Figure 2), simpler than a intracellular register and causes less damaged to the tissue. All the information about the stimulus is coded on the time location when this pulses are generated. The experiments, therefore, consist in register this timestamps synchronously with the stimulus.

In experiments with the H1, we present a preselected image moving with a velocity v(t) chosen by the experimenter (Figure 3). The motivation to this study is to elucidade the neural code used by this fly's neuron, by getting the probability P(ps(t) | v(t),h(t) ) of the neuron to fire pulses ps(t), given the stimulus v(t) and a parameter series h(t). In contrast to a physical system, the fly's biological system has the hability to adapt itself to many timescales, which can vary from milisseconds to a few minutes. It is this property that makes this system so complex and with so many chalanges to the researcher.

The contemporany scenario and our motivations

The register of the H1 generated pulses synchronously with the stimulus raises a lot of questions, but we shall approach just a few aspects. We can formulate two basic questions:

- The coding problem:

What is the mechanism that generates this pulses? - The decoding problem:

How the fly reconstruct this stimulus from the information contained on the pulses?

There are several controversies on this field. Here are some of them. Traditionally, when someone investigate the activity of a spiking neuron, it is only evaluated the firing rate. This assumes that all the information is coded in this magnitude, so this is called rate coding. Some researches has verified, however, that pulses are generated with a greater precision than the "expeted" one, and this precision of interspike interval is even grater, reaching the hundreds of milliseconds. It is possible to argue that the firing rate is all that matter to the animal, by on the reference Science 275, 1805 - 1808 (1997) we argue that this is not necessarly true, specially when a fast reaction is necessary. We show that the spikes arrive times carry much more information than thar generated by a Poisson process with the same firing rate, leading us the conclude that the spikes arrive times are important. We call thie scenario time coding. When we measure the firing rate, we have to choose a temporal window for the statistics. When the width of this interval is reduced to a few milliseconds, the time coding limit is reached. We if accept that the time coding is relevant, the discussion becomes focused on the timing precision of the pulses and the information contained on it: The organism makes use of this property or it is just an epiphenomenon? To answer that convincingly, it is needed to evaluater the animal behaviour to a set of different stimuli. We cannot, nowadays, to register the H1 activity in a movement free fly. We can, altought, use the argument that if the natural selection created an organism with this surprisingly property, it certainly makes good use of it.

Then, we may ask if the information os contained on the interval between pulses, or in a random event composed by pulses. Once we accept that the time coding is plausible, we naturally raise the question how the animal uses this spike train in a effient manner? Once the organism has the need for movement faces a very complex and variable environment, how this optical system adapt itself to the whole variety of possbile stimuli? What are the timescale to make this adaptation Nature 412, 787-792 (2001)? What are the algorithm used? What is the criterion the fly yses to maximize its resources in a hostile environment? See also Phys.Rev.Lett. 97, 178102 (2006)

It is this issues that motivate us on this research